Table of Contents

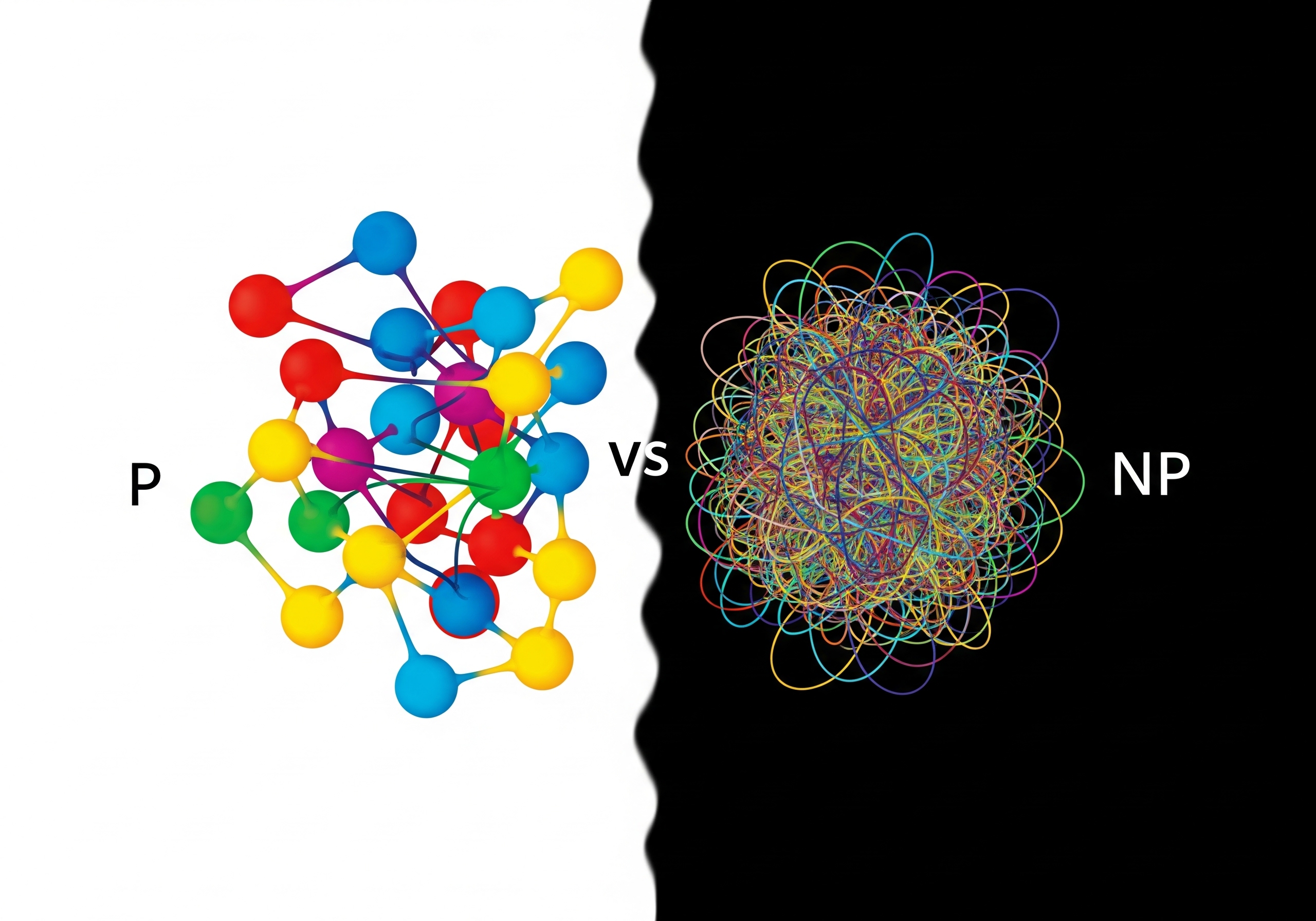

Have you ever wondered why some problems are incredibly easy for computers to solve, while others seem to stump even the most powerful machines for what feels like an eternity? The answer lies in the fascinating field of computational complexity theory, where problems are categorized based on the resources (like time and memory) required to solve them.

Today, we’ll unravel three fundamental classes: P, NP, and NP-Complete, and explore their intricate relationships.

Class P: The “Easily Solvable” Problems

The class P (for Polynomial time) includes all decision problems (problems with a “yes” or “no” answer) that can be solved by a deterministic algorithm in polynomial time.

What does “polynomial time” mean? It means that if the size of the input to the problem is n, the time it takes to solve the problem grows no faster than a polynomial function of n, such as O(n), O(n^2), or O(n^3). This is generally considered efficient and practical for real-world applications.

Example:

Imagine you have an unsorted list of n numbers and you want to find if a specific number exists in that list. A simple way is to go through each number one by one. In the worst case, you might have to check all n numbers. This is an O(n) operation, which is polynomial time. Therefore, searching in an unsorted list is a problem in P.

Another example is sorting a list of numbers. Many sorting algorithms (like Merge Sort or Quick Sort) run in O(n log n) time, which is also polynomial.

Class NP: The “Easily Verifiable” Problems

The class NP (for Non-deterministic Polynomial time) includes all decision problems for which a given solution (or “certificate”) can be verified in polynomial time.

This is a crucial distinction: NP problems are not necessarily solvable in polynomial time, but if someone hands you a potential solution, you can quickly check if it’s correct. Think of it as being easier to check an answer than to find it from scratch.

Example: Consider the Sudoku puzzle. If you’re given an empty Sudoku grid, finding the solution can be quite challenging. However, if someone gives you a completed Sudoku grid, you can quickly verify if it’s a valid solution by checking each row, column, and 3x3 block for unique numbers. This verification process takes polynomial time relative to the size of the grid. Thus, Sudoku is a problem in NP.

Another classic example is the Boolean Satisfiability Problem (SAT). Given a complex logical formula, it’s hard to find an assignment of true/false values to its variables that makes the formula true. But if you’re given such an assignment, you can quickly plug in the values and check if the formula evaluates to true.

Relationship to P: It’s widely accepted that every problem in P is also in NP (P is a subset of NP). If you can solve a problem in polynomial time, you can certainly verify its solution in polynomial time (you just solve it and check your own answer!). The big question is whether NP contains problems that are not in P, i.e., whether P = NP.

NP-Complete: The “Hardest” Problems in NP

The class NP-Complete (NPC) represents a special subset of NP problems. These are, in a sense, the “hardest” problems within NP. A decision problem L is NP-Complete if it satisfies two conditions:

Lis in NP. (Its solutions can be verified in polynomial time.)- Every other problem in NP can be reduced to

Lin polynomial time. This means that if you had a magical polynomial-time algorithm forL, you could use it to solve any other problem in NP in polynomial time.

The concept of “reduction” is key here. It means transforming an instance of one problem into an instance of another problem such that solving the second problem gives you the solution to the first.

Example: The Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP) is a famous NP-Complete problem. Given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, the problem asks for the shortest possible route that visits each city exactly once and returns to the origin city. Finding the absolute shortest route is incredibly difficult for large numbers of cities.

Why is it NP-Complete?

In NP: If someone gives you a proposed route, you can quickly calculate its total length and verify if it visits each city exactly once.

NP-Hard (reducible): It has been shown that many other NP problems can be transformed into an instance of TSP. If you could solve TSP efficiently, you could solve those other problems efficiently too.

Other well-known NP-Complete problems include the Subset Sum Problem, the Clique Problem, and the Vertex Cover Problem.

The P vs. NP Problem: A Million-Dollar Question

The relationship between P and NP is one of the most significant unsolved problems in computer science and mathematics. The question “Is P = NP?” asks whether every problem whose solution can be quickly verified (NP) can also be quickly solved (P).

If P = NP, it would mean that all those “hard” NP problems, including NP-Complete ones like TSP, actually have efficient polynomial-time solutions waiting to be discovered. This would have profound implications for cryptography (many encryption methods rely on the assumption that certain problems are hard), optimization, artificial intelligence, and drug discovery.

If P != NP, it means there are indeed problems for which verification is easy but finding a solution is inherently hard. This is the widely believed scenario.

Most computer scientists believe that P != NP, but no one has been able to prove it. The Clay Mathematics Institute has even offered a $1 million prize for the first correct proof of P = NP or P != NP.

Understanding the Hierarchy

To visualize the relationship:

P (Polynomial time)

- Problems that can be solved efficiently (in polynomial time).

- All problems in P are also in NP.

NP (Non-deterministic Polynomial time)

- Problems whose solutions can be verified efficiently (in polynomial time).

- Contains P. The big question is whether it contains problems not in P.

NP-Complete (NPC)

- A subset of NP problems.

- These are the “hardest” problems in NP.

- If you can solve any NP-Complete problem efficiently, you can solve all problems in NP efficiently (implying P=NP).

Conceptual Relationship:

- P is a subset of NP

- NP-Complete is a subset of NP

If P = NP, then all three classes (P, NP, and NP-Complete) would essentially be the same set of problems.

If P != NP (the widely believed scenario), then P is a strict subset of NP, and NP-Complete problems are the “hardest” problems within NP that are not in P.

Conclusion

The classes P, NP, and NP-Complete provide a fundamental framework for understanding the inherent difficulty of computational problems. While problems in P are efficiently solvable, the NP-Complete problems represent a frontier of computational challenge. The P vs. NP question continues to drive research, pushing the boundaries of what computers can achieve and shaping our understanding of computation itself. Whether P equals NP or not, the journey to unravel these complexities continues to be one of the most exciting quests in modern science

Start the conversation